title: PIIS2666389925002624

source_pdf: /home/lzr/code/thesis-reading/PIIS2666389925002624.pdf

Three-factor learning in spiking neural networks: An overview of methods and trends from a machine learning perspective

Szymon Mazurek,1,3,4 Jakub Caputa,1 Jan K. Argasinski, � 2,4 and Maciej Wielgosz1, *

1Faculty of Computer Science, Electronics and Telecommunications, AGH University of Krakow, Adam Mickiewicz Avenue 30, 30-059 Krakow, Poland

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2025.101414

THE BIGGER PICTURE Spiking neural networks (SNNs) represent a promising, brain-inspired paradigm for artificial intelligence, offering potential for greater energy efficiency and temporal processing capabilities. However, a key challenge lies in developing effective learning rules that are both biologically plausible and computationally powerful. Traditional two-factor rules, such as spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP), often fall short in complex learning scenarios because they lack a mechanism for integrating global feedback, such as reward signals. This perspective provides a comprehensive overview of three-factor learning rules, which address this limitation by incorporating a third, neuromodulatory signal. This signal, analogous to the function of dopamine in the brain, modulates synaptic plasticity based on global information, thereby facilitating more effective credit assignment. By reviewing the state of the art from a machine learning perspective, we bridge theoretical neuroscience with practical AI applications.

We survey the theoretical foundations, analyze various algorithmic implementations, and explore the significant impact of these rules on reinforcement learning and neuromorphic computing. This synthesis highlights how three-factor learning is not just enhancing the biological realism of SNNs but also unlocking new capabilities for creating more adaptive and robust intelligent systems. By showing current trends and future directions, we aim to accelerate the convergence of neuroscience and AI, paving the way for next-generation learning algorithms.

SUMMARY

Three-factor learning rules in spiking neural networks (SNNs) have emerged as a crucial extension of traditional Hebbian learning and spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP), incorporating neuromodulatory signals to improve adaptation and learning efficiency. These mechanisms enhance biological plausibility and facilitate improved credit assignment in artificial neural systems. This paper considers this topic from a machine learning perspective, providing an overview of recent advances in three-factor learning and discussing theoretical foundations, algorithmic implementations, and their relevance to reinforcement learning and neuromorphic computing. In addition, we explore interdisciplinary approaches, scalability challenges, and potential applications in robotics, cognitive modeling, and artificial intelligence (AI) systems. Finally, we highlight key research gaps and propose future directions for bridging the gap between neuroscience and AI.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, spiking neural networks (SNNs) have emerged as a promising paradigm in artificial intelligence (AI), inspired by the way biological neurons communicate through discrete spikes.1,2 Unlike traditional artificial neural networks (ANNs), SNNs operate in a time-sensitive manner, allowing them to model temporal patterns and perform energy-efficient computation.3,4 Despite these advantages, many challenges remain in the development of efficient learning rules for SNNs, particularly in scaling these models to complex real-world applications5–7 and developing learning algorithms that fully exploit their properties.8

2Department of Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, Jagiellonian University, Golebia Street 24, 31-007 Krakow, Poland

3Academic Computer Centre Cyfronet AGH, Nawojki Street 11, 30-950 Krakow, Poland

4Sano - Centre for Computational Medicine, Czarnowiejska Street 36/C5, 30-054 Krakow, Poland

*Correspondence: wielgosz@agh.edu.pl

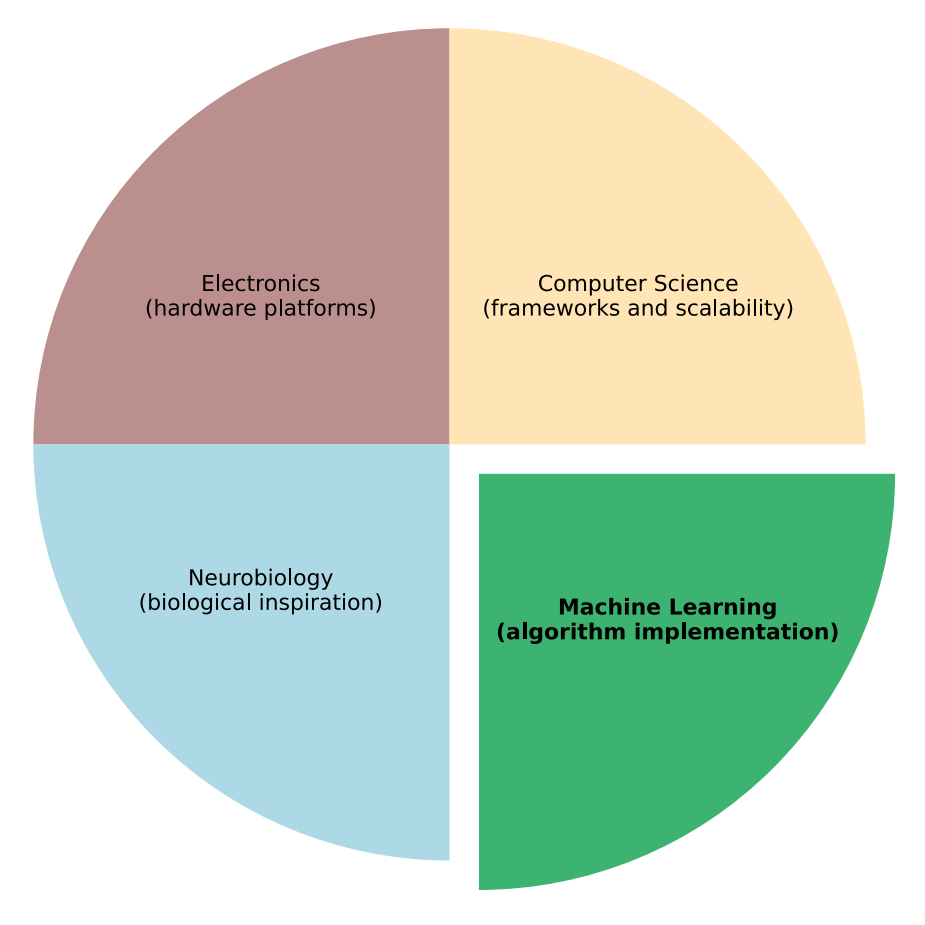

Figure 1. Spiking neural network domain and its key components, emphasizing the interdisciplinary nature required to advance the field

Three-factor learning rules draw heavily from neurobiology for their inspiration (e.g., neuromodulatory signals) and are largely implemented within the machine learning subdomain. Furthermore, their ultimate practical deployment relies on advancements in computer science (software frameworks and scalability) and electronics (neuromorphic hardware). In our work, we focus explicitly on the highlighted subdomain: machine learning.

scalability challenges for SNNs. This perspective allows us to distinguish between the principles of biological inspiration, the implementation of learning algorithms, the development of physical hardware, and the critical software and computational considerations necessary to make SNNs practically deployable.

Integration of these diverse disciplines into a cohesive framework remains a significant challenge. Differences in methodologies, terminology, and research priorities often create gaps between theoretical neuroscience, computational modeling, and hardware implementations. ML, while central to modern advancements, must balance biological plausibility, computational efficiency,

and hardware feasibility to create SNN models that are both functionally powerful and practically deployable. Figure 1 visually represents this complexity, highlighting that while ML is a dominant force, it cannot operate in isolation from the other three fields.

Consequently, this paper aims to provide a review of the state of three-factor learning from an ML perspective. In parallel, we want to emphasize the complexity of the discipline and the necessary cross-domain research collaboration to properly merge knowledge from all the fields shown in Figure 1. To achieve this, a series of papers were analyzed, highlighting the following:

- (1) Interdisciplinary perspectives: this review explores threefactor learning in SNNs from both theoretical and practical viewpoints, highlighting the convergence of neuroscience and AI.15,16

- (2) Neuromodulatory mechanisms: it emphasizes how the third factor, global modulatory signals such as dopamine, can steer synaptic changes beyond standard STDP, improving adaptive behaviors and learning efficacy.17,18

- (3) Cognitive modeling and robotics: the discussion covers real-world implications, showcasing how three-factor learning enables robust, context-aware SNN applications in tasks ranging from decision-making to autonomous navigation.19,20

- (4) Scalability and encoding strategies: it addresses key challenges in scaling three-factor learning to larger

The fundamental biologically inspired learning rule is spiketiming-dependent plasticity (STDP),9 where synaptic weights are modified based on the temporal coincidence of incoming presynaptic and generated postsynaptic spikes at the neuron. An extension of STDP and the main topic of this perspective is the three-factor learning rule, which incorporates an additional modulatory signal, often representing neuromodulators such as dopamine.10–12 This third factor plays a crucial role in guiding plasticity by integrating global contextual information, allowing the network to learn both reward signals and environmental feedback.13,14

SNN research is a complex domain that operates at the intersection of electronics, computer science, neurobiology, and machine learning (ML), as illustrated in Figure 1. Each of these fields contributes essential foundational principles for SNN development: electronics enables the design of neuromorphic hardware, computer science provides programming frameworks and scalable implementations, and neurobiology introduces knowledge about principles of biological learning mechanisms, which ML implements and optimizes.

Importantly, we acknowledge that ''computer science'' is a broad discipline that encompasses many areas, including algorithm design (which overlaps with ML) and hardware-related aspects (which are foundational to electronics). In the context of this perspective, and as visually represented in Figure 1, our use of the term ''computer science'' is specifically narrowed to its role in providing software frameworks and addressing

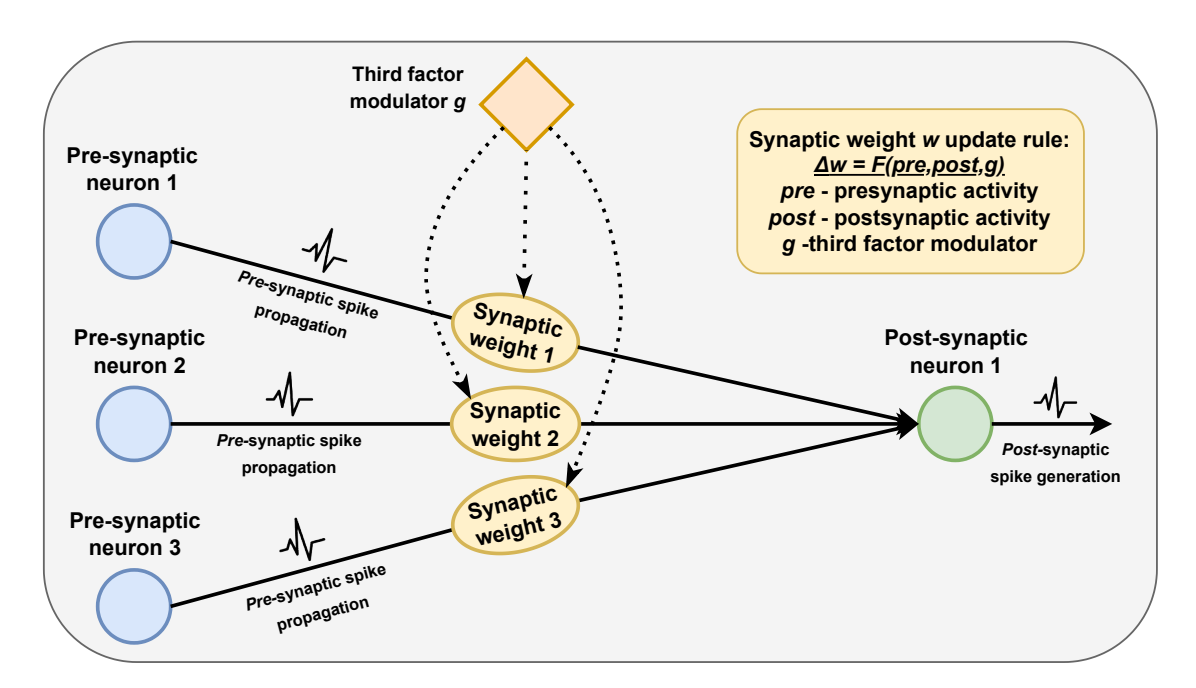

Figure 2. The general overview of the three-factor learning principle demonstrates how synaptic weights are modified based on local activity and the influence of a third factor

This third factor is crucial for integrating contextual or reward-based information, which serves as a key enhancement over standard Hebbian learning and spiketiming-dependent plasticity in spiking neural networks (SNNs). This approach constitutes a high-level method for developing training algorithms that utilize globally modulated local plasticity rules within SNN systems.

- networks, including computational constraints, diverse spike-encoding approaches, and the need for efficient hardware support.21,22

- (5) Future opportunities: finally, it describes promising avenues for cross-domain research, bridging the gaps between theoretical models and applied technologies to further advance three-factor learning in SNN.11,23

In addition to summarizing current advances, this paper identifies research gaps, offering recommendations for future directions that address these limitations through interdisciplinary synthesis. Due to the fact that three-factor learning and SNNs are still part of a widely unexplored and emerging discipline, our review approach does not strictly conform to any systematic review methodologies, such as the PRISMA or Kitchenham guidelines.24,25 In the following sections, we present and evaluate various categories that highlight different aspects of the reviewed papers. The categorization we propose is inherently approximate, as the boundaries between categories are often indistinct and overlap. Nevertheless, this classification represents our best effort to introduce a structured framework for reasoning about this highly heterogeneous, rapidly evolving, and still-nascent field.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS OF THREE-FACTOR LEARNING

The concept of three-factor learning is presented in Figure 2, with its roots appealing to biological neural mechanisms. We seek to clarify this mapping by detailing how specific neurobiological mechanisms, such as the roles of various neuromodulators and the dynamics of synaptic plasticity, are translated into the algorithmic design and functional improvements observed in SNNs.

In the human brain, learning is not solely driven by local synaptic activity but is heavily influenced by global signals, such as neuromodulators: dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine.17,26 These signals regulate synaptic plasticity, allowing the brain to adapt based on rewards, motivation, and contextual information.12,27 A visualization of this rule is shown in Figure 2.

Research in neuroscience has shown that STDP is insufficient to fully explain complex learning behaviors.10,28 The introduction of a third factor in learning models aligns with the findings on how global neuromodulatory systems interact with local synaptic processes. For example, dopamine has been linked to rewardbased learning, playing a critical role in the reinforcement learning (RL) mechanisms observed in biological systems.29,30 This inspiration has led to the development of computational models that attempt to replicate these dynamics in artificial SNNs14,31 by combining various algorithmic implementations of local learning rules, such as STDP, with third-factor signals, carrying information about the global state of the neuronal system.

The concept of three-factor learning has evolved over several decades and is shaped by both theoretical and experimental advances. Early research on synaptic plasticity emphasized twofactor models, such as Hebbian learning and STDP.9,13 However, these models faced limitations in explaining reward-driven behaviors and long-term adaptations observed in biological systems.17,32

In the late twentieth century, neuroscientists began to uncover the role of neuromodulators, such as dopamine, in RL.33,34 The

discovery of dopamine involvement in reward prediction errors led to the formulation of models that incorporated an additional global factor in synaptic updates.15,35 These models demonstrated improved learning capabilities in both simulations and empirical studies.7,36

By the early 2000s, the computational neuroscience and ML communities started to converge on the importance of three-factor learning. Research focused on developing algorithms that balance local synaptic updates with global feedback signals, resulting in enhanced performance for tasks that require long-term planning, decision-making, and contextual adaptation.21,37 Today, three-factor learning is recognized as an important component in bridging the gap between biological plausibility and artificial learning systems.11,38

Currently, the field of three-factor learning in SNNs is characterized by a growing consensus on the importance of integrating local and global learning signals.16,39 Researchers have developed various algorithms that take advantage of neuromodulatory influences to improve network adaptability and learning efficiency.3,40 These advancements have contributed to improved performance in tasks requiring temporal memory, reward-based learning, and complex decision-making.5,6,41

Experimental studies have shown that incorporating threefactor learning mechanisms can enhance the stability of network dynamics.18,42 This is particularly important in tasks where networks must balance exploration and exploitation or operate under delayed reward conditions.19,43 Computational models now commonly simulate neuromodulatory effects, enabling more biologically plausible learning processes.44,45

Despite these improvements, several challenges remain. Scalability for large networks, the design of efficient hardware platforms, and the use of real-world datasets are areas where further research is needed.46,47 Furthermore, there is ongoing work to unify disparate approaches under a cohesive theoretical framework that connects biological mechanisms with artificial implementations.48,49 As a result, current research is focused on cross-disciplinary efforts that aim to refine both the theoretical understanding and practical applications of three-factor learning.1,11

Neuromodulatory influence on synaptic plasticity

Neuromodulation plays a crucial role in synaptic plasticity by integrating intrinsic and extrinsic signals that affect neuronal interactions and learning dynamics. In this section, we will formalize the learning rules discussed and show how synapse modulation could be manifested on the basis of insights from neuroscience.

STDP and effects of third-factor modulation

The STDP can be regarded as an application of Hebb's postulate,9 worded as ''neurons that fire together, wire together.'' This intuitive statement indicates that synapses for which presynaptic and postsynaptic spiking activity coincide temporally result in a synaptic weight change:

$$\Delta w_t = \begin{cases} e^{-\Delta t/\tau_+}, & \Delta t > 0 \\ e^{\Delta t/\tau_-}, & \Delta t < 0 \end{cases}$$

(Equation 1)

where Δwt is the change in synaptic weight at time t, Δt = tpost − tpre is the timing difference between pre- and postsynaptic spikes, and τ+ and τ− are time constants that control the decay of the STDP window.

Thus, if presynaptic spikes directly precede postsynaptic spikes, we observe long-term potentiation (LTP), resulting in an increase in synaptic weight. If the opposite is true, long-term depression (LTD) occurs, and the synaptic weight decreases. The shape of LTD and LTP windows is controlled by the hyperparameter τ.

In general, we can simplify the above equation as a function of presynaptic and postsynaptic spikes:

$$\Delta w_t = H(t_{pre}, t_{post}),$$

(Equation 2)

where H(⋅) is a function governing synaptic plasticity. The introduction of the third factor extends the STDP rule in the following form:

$$\Delta w_t = H(t_{pre}, t_{post}, g_t),$$

(Equation 3)

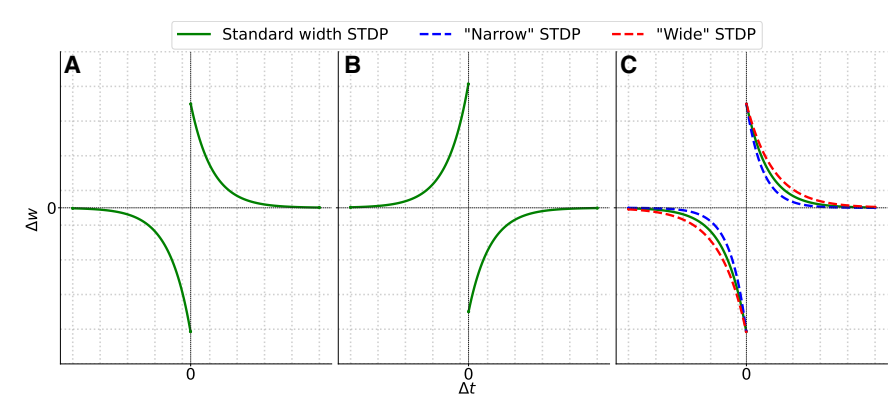

where g is the modulatory signal affecting the neuron at time t. This third-factor signal can broadly influence the dynamics of base synaptic plasticity.26 Based on neurobiological knowledge,12 synaptic neuromodulation can induce effects such as amplifying the weight change, reversing the STPD window (swapping LTD with LTP on the timescale), changing the widths of the LTP and LTD windows, or even gating the occurrence of a synaptic weight modification. Visualization of these exemplary effects can be seen in Figure 3.

Spatial and temporal aspects of third-factor modulation

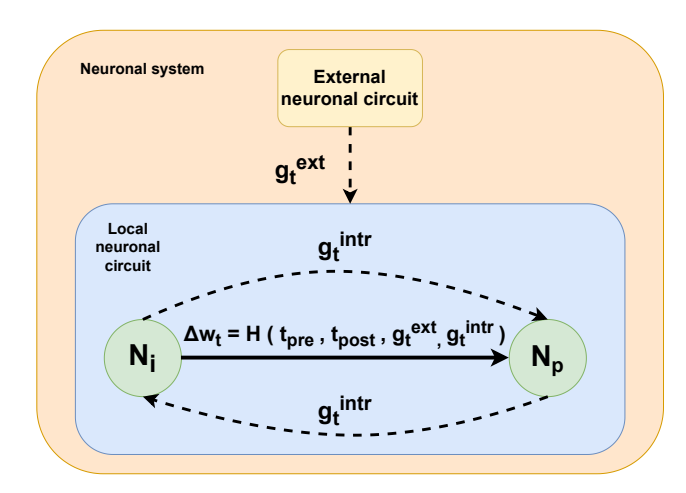

One of the fundamental problems with respect to the use of three-factor learning rules is the spatial and temporal aspects of modulatory signal effectiveness. The relationships between neuromodulators in these domains are notoriously complex and difficult to observe in biological systems.26 Although the temporal properties of modulatory signals have already been incorporated into the discussed equations, spatial properties should also be included. Thus, we refer to the concepts of intrinsic and extrinsic neuromodulation, which are graphically described in Figure 4.

Intrinsic neuromodulation

Intrinsic neuromodulatory signals are exchanged between neurons within the same neuronal circuit. Neurons are considered to be within the same local network if they coincide26 in one of the following ways.

- (1) Spatially, when they are physically close to each other within a specific region of the brain or a neural circuit. Their proximity allows for direct and rapid communication, often forming dense local connections.50

- (2) Functionally, when they work together to perform a specific task or contribute to a common computation. They might be located in different physical locations but are interconnected and co-activated during particular brain activities, such as processing a specific type of sensory input or generating a certain motor output.51

- (3) Morphologically, when they have similar structural characteristics, such as their shape, dendritic branching patterns, or axonal projections. Neurons with similar morphology often have similar physiological properties and connectivity patterns, leading them to be part of the same functional unit or local circuit.52

Patterns Perspective

Figure 3. Possible influences of third factor on spike-timing-dependent plasticity learning rule

(A) This plot shows baseline spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP), where synaptic weight change $(\Delta w)$ depends on the relative timing $(\Delta t)$ of pre- and postsynaptic spikes.

(B) This plot illustrates reversed STDP, where the LTD and LTP polarities are flipped.

(C) This plot demonstrates STDP shape modulation, where neuromodulatory factors influence the temporal profile of plasticity, modifying the learning window width. This highlights the numerous possibilities for how the third factor can influence local learning rules when designing raining algorithms for spiking neural networks (SNNs). By modulating the STDP window, the third factor (representing signals like dopamine) en-

ables SNNs to exhibit more complex and biologically plausible learning behaviors, such as reward-modulated plasticity or context-dependent learning, which are essential for tasks in reinforcement learning and cognitive modeling.

It can be said that intrinsic neuromodulation serves as a "memory" that adjusts the dynamics of the local network based on its recent and current activity. 53 An intrinsic neuromodulatory signal can be described as

$$g_t^{\text{intr}} = f_{\text{intr}} \left( N_t^i, N_t^p, S_t^{\text{intr}} \right),$$

(Equation 4)

where $f_{\text{intr}}$ describes how the state $S^{\text{intr}}$ of the internal network determines the local neuromodulatory effect between neurons $N^{i}$ and $N^{p}$ at time t.

Extrinsic neuromodulation

Signals from external neural networks influence other circuits by providing information on their ongoing activity. $^{53}$ The modulatory signal that affects a population of neurons P at time t can be defined as

$$g_t^{\text{ext}} = f_{\text{ext}}(P_t, S_t^{\text{ext}}),$$

(Equation 5)

where S^{ext} is a state of the external neuronal circuit.

Extended synaptic plasticity function

Based on the concepts discussed so far, we can formulate a more detailed model for synaptic plasticity, which incorporates weighted contributions from different factors, as well as spatial and temporal properties of all signals influencing plasticity of a given synapse.

$$\Delta W_t = H(t_{pre}, t_{post}, g_t^{intr}, g_t^{ext})$$

(Equation 6)

This formulation highlights how intrinsic and extrinsic neuromodulatory factors contribute to synaptic plasticity, ultimately shaping learning and adaptive behaviors in neural networks. We note that the presented equations can be further extended and that their presented derivation is not exhaustive due to the complexity of the plasticity phenomena.

A note on backpropagation through time

While three-factor learning rules offer a biologically plausible approach to training SNNs, it is important to acknowledge the role of backpropagation through time (BPTT) based on surrogate gradients. 54,55 Both of those topics are extensive and beyond the scope of this perspective, yet we will briefly describe them to provide an overview of the problems encountered when training SNNs and their relationship with biologically plausible

learning methods. The surrogate gradient method enables gradient-based learning in SNNs by approximating neuron spiking activity with a continuous function, which allows error backpropagation. 56 BPTT enables one to perform backpropagation in the temporal domain, which is inherent in SNNs. The combination of these methods allows for effective training of deep SNN architectures with the well-known approaches established in deep learning research. Furthermore, the performance achieved when using them is robust, closely compared to that observed with classic deep neural networks.2 Recent empirical studies demonstrate that BPTT, combined with surrogate gradient methods, has achieved high performance across a wide spectrum of tasks, benefiting from optimized software and hardware support.57 However, BPTT in its standard form, based on direct derivative computation over time, faces several challenges. Firstly, the computational cost and memory footprint of BPTT can be substantial, especially for long input sequences, due to the need to store neuron states at each time step. This also implies relatively slow processing, as the system-gradient computation for consecutive steps—is sequential in nature. Secondly, BPTT can suffer from problems with the stability of the training process, as vanishing or exploding gradients can hinder the learning of long-range temporal dependencies.58 Lastly, BPTT is limited in terms of online learning, as it requires an original input sequence to be available before the error is backpropagated, thus making it non-causal. In general, BPTT is considered biologically implausible, as it deviates from the local learning mechanisms observed in the brain.59 The ongoing research aims to address these limitations by exploring memory-efficient BPTT techniques, such as activation checkpointing and truncated BPTT, 59,60 and developing more biologically inspired approximations, such as local learning rules and eligibility trace propagation.5,6,61 Despite the highlighted shortcomings of BPTT in its classical form, there are efforts to bypass them. BPTT can be considered as a general group of algorithms that are capable of propagating the global error signal over time. These approaches leverage a BPTT-like mathematical foundation to derive online and biologically plausible learning rules for SNNs. This new perspective challenges the traditional dichotomy between BPTT and local Hebbian-style plasticity rules. A prominent example of such an approach is an E-prop algorithm, 5,6 an online learning method that leverages a

Figure 4. Different sources of the top-level third factor

The signal can be emitted intrinsically between neurons in the same neuronal circuit or extrinsically, when the signal arrives from outside of the circuit. Neurons that coincide spatially, functionally or morphologically are considered to be in the same circuit. 26 Understanding these spatial and temporal aspects is crucial for designing SNNs that can leverage both local network dynamics and global contextual cues for improved credit assignment and adaptive behaviors, mirroring biological learning processes.

mathematical refactoring of gradient descent, similar to BPTT, but in a biologically plausible manner. It replaces the need for backward-in-time propagation with a combination of eligibility trace based on local spiking activity and global learning signals, closely matching the performance of derivative-based BPTT. Currently, BPTT based on surrogate gradients remains the primary method of training SNNs. However, a growing body of research on robust and backpropagation-free methods, such as E-prop, offers the potential to increase speed, scalability, and energy efficiency while maintaining competitive performance. Such advancements would unlock numerous applications for SNNs, particularly in resource-constrained environments and online learning scenarios.

RESEARCH TRENDS

The role of neurobiology in development of bio-inspired learning rules

In this section, we describe the fundamental neurobiological principles that have influenced the design and development of bio-inspired learning rules, with a particular focus on three-factor learning. We explore how advances in understanding neuromodulation, synaptic plasticity, and neural circuit function provide the foundation for these algorithms. By examining these mechanisms, we aim to illustrate the origins of three-factor learning and underscore the importance of incorporating such biological complexity to enhance the plausibility and capabilities of artificial learning systems. Advances in neuroscience have contributed to our understanding of neuromodulation, synaptic plasticity, and neural circuit function. From the perspective of three-factor learning, knowledge on how neuromodulators such as dopamine, acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and serotonin influence neural activity, synaptic plasticity, and learning 16,26 has greatly influenced the development of such algorithms. In biological

systems, neuromodulators influence plastic changes based on reward signals, errors, and contextual information. 11,62 Studies have shown that neuromodulators can alter the shape and polarity of STDP windows and regulate neuron excitability, firing patterns, and tuning curves. 12,36 Specific findings include the roles of dopamine in reward processing, motivation, and memory robustness, as well as acetylcholine's contribution to attention and learning rate.27,63 Furthermore, research has highlighted the interaction of multiple neuromodulators, emphasizing their role in coordinating different aspects of cognitive functions and behavior. 10,64 Synaptic plasticity research has further deepened our understanding of mechanisms such as STDP and its variations, such as reward-modulated STDP (R-STDP).2,4 Neuromodulators have been shown to gate or modulate STDP, influencing synaptic changes by regulating calcium influx and excitatoryinhibitory balance in neural circuits. 18,65 Studies have also explored how different brain regions, such as the hippocampus, cortex, and basal ganglia, contribute to cognitive functions such as working memory and attention. 13,66 Models have demonstrated how cholinergic and GABAergic modulation enhances visual attention and memory stability. 63,67 Neuromodulation has been shown to play an important role in homeostatic plasticity, the crucial set of mechanisms that maintain stable neural network function in the face of ongoing synaptic plasticity and activity changes. 68,69 Although synaptic plasticity (Hebbian) is essential for learning, homeostatic plasticity counteracts potential instability by regulating neuronal excitability and synaptic strength.68,70 This regulation prevents runaway potentiation or depression, ensuring that the activity of the system remains within a functional operating range. 71,72 Key homeostatic mechanisms include synaptic scaling, which globally adjusts synaptic strength, and intrinsic plasticity, which modifies the intrinsic excitability of a neuron. 73,74 Neuromodulators influence these homeostatic processes. For instance, dopamine can modulate synaptic scaling and intrinsic excitability, affecting the stability and plasticity of developing neural circuits. 75,76 Serotonin plays a role in the regulation of excitation-inhibition balance, a critical aspect of network homeostasis.69 Acetylcholine contributes to firing rate homeostasis and interacts with synaptic scaling mechanisms.77,78 Although the primary form of plasticity discussed in ML with SNNs and in this perspective is related to synaptic plasticity, we note the possibility of including homeostatic plasticity when developing novel algorithms. The interplay between neuromodulators, synaptic plasticity, and homeostatic mechanisms underscores the complexity of biological learning. Three-factor learning algorithms in SNNs, inspired by these principles, offer a powerful framework to capture this complexity. However, to truly emulate biological intelligence, future research must move beyond isolated mechanisms and strive for a more holistic integration. This includes developing models that account for dynamic interactions between different neuromodulators, context-dependent modulation of STDP, and the stabilizing role of homeostatic processes.

Three-factor learning algorithms

A wide range of learning algorithms has been explored in SNNs, many inspired by biological mechanisms. Three-factor learning rules have gained prominence, introducing a third element, such as neuromodulators or error signals, to improve synaptic

updates.10,11,62 The fundamental motivation behind three-factor learning stems from the need to model biological neural plasticity more accurately. Traditional learning approaches often struggled to capture the complex mechanisms of synaptic modification observed in biological systems. By introducing a third factor, typically a neuromodulatory signal, error signal, or reward signal, researchers have developed more sophisticated learning algorithms that can adapt more dynamically to environmental contexts. In this section, we describe a selection of research articles that demonstrate the applicability of three-factor learning in solving ML tasks. Several key approaches have emerged in the development of three-factor learning rules. In Fre´ maux et al.,29 the authors analyze the functional requirements for R-STDP using a simple set of neurons. They compare R-STDP and R-max STDP, where the reward signal acts as an additional multiplier of the change in synaptic weight, delivered at the end of a task to indicate success. Through trajectory learning and spike train response tasks, they explore the theoretical underpinnings of reward-modulated plasticity, concluding that effective rewardbased learning requires a small unsupervised term influence, sensitivity to reward timing, and a reward prediction mechanism. RL principles have been particularly influential in three-factor learning strategies. In Fre´ maux et al.,15 the authors propose a continuous-time actor-critic framework for RL in SNNs. They explicitly model temporal credit assignment using temporal difference (TD) learning, where synaptic plasticity is modulated by TD error. The approach integrates value and policy networks with R-STDP. They evaluated their method in challenging RL tasks, including Morris water maze navigation, acrobot, and cartpole simulations, demonstrating the effectiveness of their approach in complex motor control scenarios. Vasilaki et al.79 explored spike-based RL in continuous state and action spaces, addressing cases where traditional policy gradient methods fail. They propose a feedforward SNN model in which reward modulates the probability of firing sequences propagating from place cells (representing agent position) to action cells (controlling movement). Synaptic changes are driven by STDP, modulated by a biologically plausible third-factor reward signal. The model is tested in a simulated water maze task, showcasing its potential for sophisticated spatial navigation learning. More recent developments have pushed the boundaries of three-factor learning. In Bellec et al.,5,6 the authors introduce the E-prop algorithm, with the aim of approximating BPTT for global error projection. They take inspiration from the error-related negativity, a signal that immediately follows the erroneous behavior in the brain.80 The algorithm achieves results close to BPTT on a variety of tasks, including speech recognition, word prediction, oneshot learning, and pattern generation. Building on these foundations, Liu et al.41 propose MDGL (multidigraph learning rule), an innovative algorithm to propagate top-down error signals to specific neurons in the network, which then propagate them further in their local neighborhood. Through comprehensive evaluation, they demonstrate that their method closely matches BPTT and outperforms E-prop in online learning and pattern generation tasks. In a notable contribution, Schmidgall and Hays46 show an interesting approach of using signals obtained with metalearning to modulate STDP, which is optimized by gradient descent. The synaptic change occurs when a neuromodulatory signal appears. They demonstrate the robustness of their solu-

tion by evaluating the network in T-maze navigation, character recognition, and cue association tasks. Barry et al.48 developed a method using modulated STDP to gate plasticity, introducing a surprise signal derived from error. Their approach involves inducing synaptic changes whenever a surprise signal arrives. Through rigorous testing in continual learning and rule-switching scenarios, they showcase the system's ability to rapidly adapt while maintaining operational stability. Quintana et al.81 propose a novel event-based three-factor local plasticity (ETLP) method tailored for online learning with neuromorphic hardware. Their approach features a unique architecture where hidden layers update weights through random matrices, and the output neurons are connected one to one to excitatory and inhibitory synapses. Evaluated on pattern recognition tasks using N-MNIST and SHD datasets, ETLP achieves competitive classification accuracy with lower computational complexity compared to global methods such as BPTT and E-prop. These algorithms collectively aim to improve performance on tasks that require temporal memory, decision-making, and context-sensitive learning, with a strong emphasis on mimicking the mechanisms found in natural neural systems. This emphasis reflects a broader trend toward integrating both local synaptic updates and global modulatory signals to improve the scalability and efficiency of learning in SNNs.5,6,37 A comparison of three-factor learning algorithms and their applications is shown in Table 1.

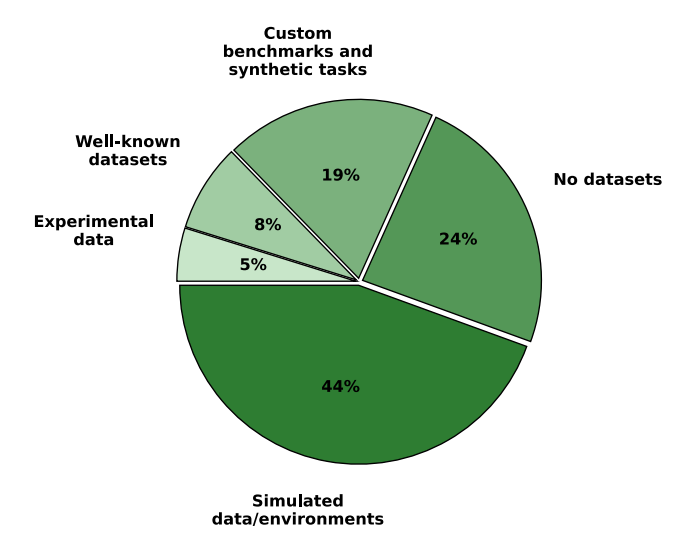

Datasets

Given the inherent heterogeneity and the involvement of multiple domains in three-factor research, the characteristics and types of datasets used exhibit significant variation, as presented in Figure 5. A significant number of studies are based on synthetic or custom-designed benchmarks, which allow precise control of experimental variables.48,90 These datasets simulate tasks such as navigation (e.g., 1D and 2D multi-target tasks), robotics (e.g., robotic arm reaching and terrain crossing), cognitive tasks (e.g., working memory, decision-making, and attention), and pattern recognition.44,46 Custom tasks such as rule-switching, memory-guided saccades, and associative learning are also common.33,63

In contrast, some studies4,38,81 incorporate well-known ML datasets such as MNIST,93 Caltech-256,94 ETH-80,95 and NORB96 for image recognition or SHD97 for speech analysis. Some of those datasets, especially in image recognition, are adapted to have the properties of recordings gathered with native neuromorphic sensors. An example of such adoption is the N-MNIST dataset,98 used by Quintana et al.81 There are also cases, especially in neuroscience research, in which experimental data from biological studies are used, including cortical slice recordings, optogenetic experiments, and natural scene videos.18,34 However, such studies focus on discovering biological mechanisms in living systems. Although they remain crucial for the discovery of bioplausible learning mechanisms, such studies often do not attempt directly to train SNNs to solve a specific task using the discovered phenomena. Thus, it can be observed that real-world datasets remain underutilized, particularly in studies focusing on theoretical models and neural mechanisms.22,99 This indicates a trend toward task-specific simulations over standardized benchmarks. In the future, there is a growing need to validate models through greater use of

(Continued on next page)

| Article | Learning algorithm | Task | Dataset | Performance | Network size | Platform |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rostami et al. 89 | E-prop | KWS (keyword spotting) | Google Speech Commands |

91.2% accuracy | 20–360 neurons | neuromorphic chip |

| Zambrano et al. 90 | CT-AuGMENT | saccade tasks, match to category, motion tasks |

simulated data | 95%–99% high convergence rates |

14–22 neurons | CPU/GPU |

| Barry and Gerstner 48 | SpikeSuM | volatile sequence tasks with rule switching | simulated data | up to 100% detection | up to 1,000 neurons | CPU/GPU |

| Schmidgall and Hays 46 | Meta- SpikePropamine |

cue association, one-shot classification | simulated and character recognition dataset |

95.6% (cue); 79.6% (char) |

20–196 neurons | CPU/GPU |

| Mikaitis et al. 91 | dopamine- modulated STDP |

Pavlovian conditioning | simulated data | not stated (efficiency focus) |

10–10,000 neurons, 10 M synapses |

neuromorphic chip |

| Frenkel et al. 92 | feedforward eligibility traces |

hand gesture, KWS, navigation |

IBM DVS Gestures, SHD, synthetic |

87.3% (gestures), 90.7% (KWS), 96.4% (nav) |

up to 256 neurons, 64,000 synapses |

CPU/GPU |

| Vasilaki et al. 79 | modulated STDP | Morris water maze | simulated data | solved task correctly | 700 neurons | CPU/GPU |

| Legenstein 37 | reward-modulated STDP |

3D cursor control | experimental data | reproduced credit assignment; good agreement |

480 neurons | CPU/GPU |

The performance of other learning algorithms that are often included comparatively are not included in the table. RMSE, root-mean-square error.

Figure 5. Datasets used in research papers investigating threefactor learning in spiking neural networks

The prevalence of custom and simulated datasets in three-factor SNN research, as shown in this figure, highlights a current limitation in the field. To ensure the robustness and real-world applicability of three-factor learning algorithms, there is a clear need for greater utilization of standardized, real-world neuromorphic datasets, which would facilitate more comparable and rigorous evaluation of learning performance.

real-world data, ensuring that the proposed learning algorithms are robust in diverse environments and applications.7,19 Furthermore, applied SNN research would greatly benefit from establishing a wide set of standard neuromorphic datasets, comparable to MNIST or ImageNet for classic deep learning. The number of such datasets is growing,97,98 yet it remains a challenge, often demanding specialized neuromorphic hardware and precise experimental setups. In addition, SNN applications span various domains, making standardization a persistent challenge.

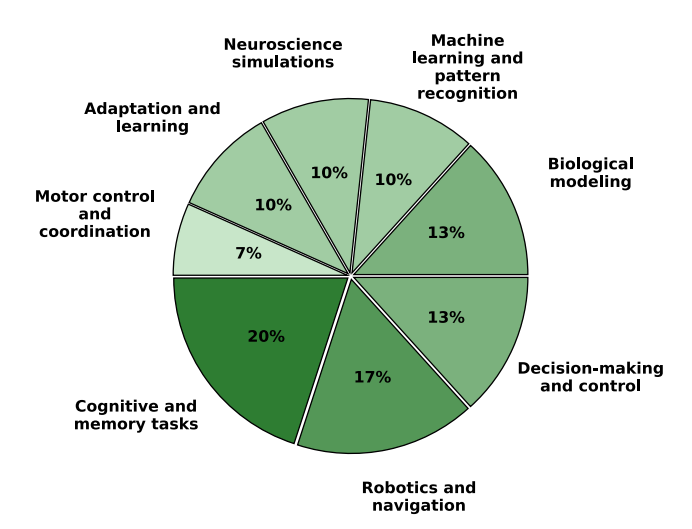

Application domains

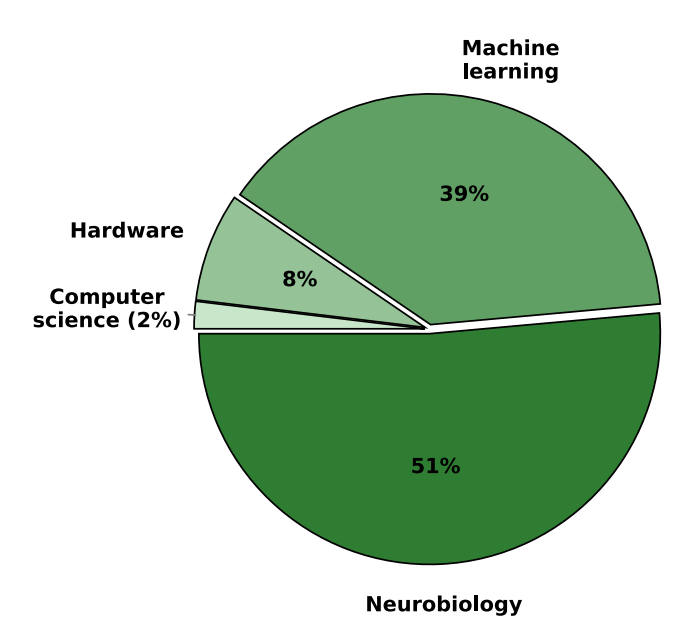

Research on three-factor learning in SNNs spans multiple scientific and technological domains, with neuroscience and neurobiology forming the foundation of many studies.26,30,34,66 An important line of study is the modeling of neural circuits in brain regions, such as the hippocampus, cortex, and basal ganglia, to investigate the mechanisms underlying synaptic plasticity: STDP, neuromodulation, and neurotransmitter influences.16,42,100,101 Biological studies on three-factor learning rules highlight the ability of these algorithms to better capture cognitive processes such as memory, attention, decision-making, and brain rhythms.11,18,33,102 Many of these approaches are validated with experimental data from in vitro and in vivo studies, showing the occurrence of such processes in living neural systems.29,79 Beyond neuroscience, three-factor learning is explored in the domains of ML, robotics, and neuromorphic computing.1,5,6,38,83 Traditional Hebbian and STDP-based learning often struggle with credit assignment over long timescales and stability, whereas three-factor learning integrates a modulatory signal that refines synaptic weight updates based on task-relevant feedback.103,104 These algorithms are particularly promising for tasks that require real-time decision-making, continuous learning, and resilience to environmental changes. Robotics and cognitive modeling have also benefited from three-factor learning. Neuromodulated SNNs enable adaptive motor control, navigation, and sensor fusion, allowing agents to operate effectively in dynamic environments.20,23,43,46 Many studies develop neuromorphic controllers that incorporate reward-modulated plasticity for RL, optimizing behavior through experience-dependent synaptic changes. In computer vision and sensory processing with SNNs, three-factor learning has been applied to pattern recognition, object classification, and feature extraction.4,41 Compared to pure STDP, these approaches improve generalization and robustness, particularly in unsupervised or RL settings. Other research explores affective computing, where neuromodulation is used to simulate adaptive emotional responses in AI systems, influencing decision-making and learning strategies.31,43 Lastly, a growing area of interest is neuromorphic hardware, where SNNs with three-factor learning are being implemented on specialized architectures for energyefficient computation.4,83,92,105 Such solutions enable effective inference and on-chip learning, crucial in domains such as robotics. In the following sections, we discuss the topics related to dedicated hardware for three-factor learning. In Figure 6, we try to summarize the distribution of the research domains in the papers we focus on in this perspective. Additionally, in Figure 7, we show the distribution of scientific disciplines that are predominant across the reviewed papers. In the context of the theoretical domain division in SNN research, as presented in Figure 1, we can see that the field of three-factor learning is predominantly analyzed from the perspective of neurobiology and ML, leaving the electronics (hardware) and computer science (computational aspect) relatively underrepresented, showing the need for further research.

Applications in AI and robotics

Neuromodulation and three-factor learning have influenced advances in AI and robotics, with applications focusing on adaptive control and navigation. Studies highlight how neuromodulated learning enables robots to navigate, avoid obstacles, and manipulate objects in dynamic environments.19,20 Adaptive robotic control can be achieved through three-factor learning rules in SNNs, allowing robots to learn and adjust to new terrains and tasks in real time.23,48 Some models use hierarchical control structures inspired by biological systems, such as the nervous system of Aplysia, to enhance autonomous navigation.14,45 In addition, emotion-modulated RL has been explored to improve robot adaptability by adjusting learning rates and reward predictions based on neuromodulatory influences such as dopamine and acetylcholine.31,64 The integration of real-world sensors with neural networks further supports adaptive behavior in complex environments, where rapid adaptability and online learning are crucial.7,22 Neuromodulation in SNNs can also be achieved using RL, an established method in the field of robotics and autonomous systems.106 Actor-critic frameworks and R-STDP can be used to improve temporal credit assignment and decision-making processes.42,104 Continuous-time RL mechanisms, combined with working memory features, enable evidence accumulation and better control of agents in dynamic scenarios.41,90 Cognitive and affective AI applications focus on neuromodulated architectures that simulate emotional influences, using neurotransmitter analogs such as dopamine and serotonin

Figure 6. Application domains of SNN research reviewed in this work

The significant percentages in areas like robotics and navigation, cognitive and memory tasks, and decision-making and control underscore the potential of three-factor learning for creation of adaptive and biologically plausible AI systems capable of complex behaviors in dynamic environments.

to improve creativity, decision-making, and memory allocation.31,43 Lifelong learning is also supported by mechanisms such as surprise-modulated plasticity and controlled forgetting through dopaminergic modulation.17,49 Additional studies apply these innovations to pattern recognition, image classification, and decision-making tasks, often optimizing neuromorphic

Figure 7. Primary scientific domain across reviewed research articles in the domain of three-factor learning, highlighting the strong foundational role of neurobiology and ML in the current landscape of three-factor learning research

The relatively smaller contributions from computer science and hardware signal a need for further interdisciplinary research to fully realize the potential of three-factor learning in scalable and energy-efficient neuromorphic computing.

hardware models to improve energy efficiency and scalability.4,47 These advances reflect a multidisciplinary effort to create biologically inspired, robust, and adaptive systems capable of real-time learning and adaptation in uncertain environments. Thus, SNNs using three-factor learning show promise for advancing the domain of edge devices and robotics, especially because of their remarkable energy efficiency and adaptability.

Scalability considerations

Scalability is a critical challenge in all computational methods, including SNNs. However, in the domain of SNNs, measurement of computational complexity and required resources is much more challenging than for any software deployed on CPUs or GPUs. The reason for this is the unique and asynchronous mode of operation of these networks, as neuronal signals are propagated sparsely over time. Thus, full exploitation of their properties is tightly coupled with the neuromorphic hardware that is used to deploy them. The co-design of software and hardware in SNNs is beyond the scope of this perspective, yet the awareness of its importance is growing.92,105,107,108 Currently, most research in the domain of SNNs and three-factor learning either omits the computational complexity of proposed algorithms or tries to summarize it using the theoretical number of operations performed during the runtime. However, standard complexity measures, such as floating-point operations (FLOPs), commonly used in deep learning, are insufficient for SNNs due to their fundamentally different mode of computation. Unlike ANNs, which perform dense matrix multiplications at each layer, SNNs operate in an event-driven manner, where computations are sparse and depend on spike occurrences. A common alternative is to count the number of accumulated operations, which refer to additions performed when integrating spikes incoming to a neuron.109 This contrasts with traditional ANNs, where operations typically involve multiply accumulate (MAC) computations due to weight multiplications in dense layers. In some cases, authors also rely on classical big-O complexity analysis.81 Although useful for rough estimations, such methods remain limited because they do not account for hardware-specific optimizations, memory constraints, or differences in execution models, all of which can significantly impact the real-world efficiency of SNN implementations.105,110,111 Scalability and computational requirements are necessary to fully evaluate the system's usefulness when deployed; therefore, establishing reliable metrics is necessary. We envision that in the future, measuring computational efficiency and scalability of SNNs, together with the used learning algorithms, will inherently depend on the used neuromorphic platform.

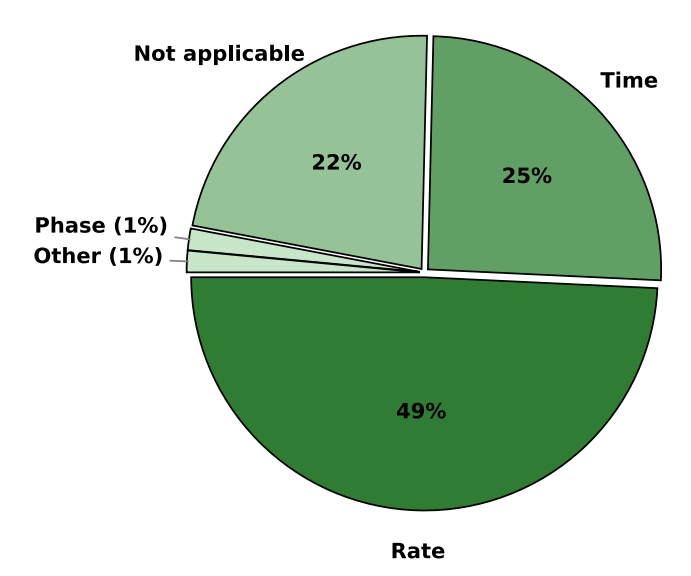

Encoding methods

Methods of encoding analyzed data in spike trains that serve as input to SNN play a fundamental role in determining their performance and efficiency.112 Neuroscience research has discovered that neurons use numerous encoding schemes in the brain.113–116 While important, their full description is beyond the scope of this perspective. Thus, we will briefly describe only the selected ones to highlight their trade-offs and complementarity, as well as popularity in three-factor learning research. Rate encoding is the most widely used encoding method in SNN research in general. It represents information through the

Figure 8. Overview of input-encoding methods in SNNs, highlighting the predominance of rate encoding and the increasing adoption of time-based and hybrid encoding strategies

The choice of encoding method directly influences how temporal spike patterns interact with neuromodulatory signals in three-factor learning rules, impacting the learning efficiency and biological plausibility of SNN models. The limited adoption of adaptive and phase encoding suggests potential areas for further exploration to enhance the expressiveness of SNNs using three-factor learning.

frequency of spikes, making it simple and compatible with neuromorphic hardware. It is also easily used for converting nontemporal data into the spiking representation. Using the example of static images, the intensities of individual pixels are treated as probabilities of spike occurrence in a given timestep. Temporal encoding methods leverage precise spike timing to convey information. They exist in many variations, but the core idea behind them is to emphasize the spikes that arrive earlier as the ones carrying more information.117 Temporal encoding methods usually lead to lower computational complexity, as the network emits a lower number of spikes.112 Lastly, we note the idea of fully adaptive encoding. It refers to the set of methods that employ parametrized neural network layers that can learn the spike representation of input data.46 It is still rarely used among SNN researchers, yet neuroscientific evidence shows its importance in biological neural systems, indicating the possibility of further exploration.118 It is important to note that the type of encoding can be related to input data encoding or intraneuron communication in the network. However, most often, the same encoding is applied for both cases. Each encoding strategy presents trade-offs between efficiency, biological plausibility, and ease of hardware implementation. Figure 8 provides a summary of the encoding methods used in the literature analyzed in this perspective. We consider only the type of input encoding, which, in most cases, also translates to neuronal communication in the network.

The distribution of encoding methods shown in Figure 8 underscores the widespread reliance on rate encoding, which constitutes almost 50% of the approaches used in the research of the analyzed papers. This prevalence comes from its straightforward implementation and compatibility with neuromorphic hardware, despite its relatively lower temporal precision and increased computational cost.112 Time-based encoding follows as the second most utilized method, at 25.4%, reflecting the increasing emphasis on spike timing as a means of improving computational efficiency. Phase encoding and adaptive encoding were used in only 1.5% of the articles for both methods. Although beneficial, their lower popularity may indicate that the use of such encoding methods is yet to be explored. The remaining 22.4% of articles were related to experimental neuroscience, simulations of neuronal dynamics, or other studies where input encoding was either not explicitly stated or not directly relevant. This distribution suggests that, while rate-based encoding remains dominant, alternative strategies, particularly time-based approaches, are gaining traction as researchers explore more efficient and biologically plausible representations of neural information. This is especially relevant when considering the deployment on specialized hardware, where relying solely on rate coding can lead to increased computational cost.112 Additionally, increasing the expressiveness of SNNs would require further exploration for determining optimal neural coding patterns both for input data and neuronal communication. Finally, we emphasize that the uniqueness of three-factor learning methods lies also in their general applicability for synaptic plasticity rules, irrespective of the chosen encoding method.

Hardware and computational platforms

The development in the design and manufacturing of neuromorphic hardware has led to the emergence of numerous applications that deploy SNNs on such chips.119 This choice of computing platforms significantly impacts the scalability and efficiency of SNN simulations. While traditional platforms such as CPUs and GPUs dominate, neuromorphic hardware is gaining attention for its potential in energy-efficient processing. The overview of neuromorphic chip research utilizing three-factor learning can be seen in Table 2. Despite the growing number of SNN applications on neuromorphic chips, examples of applications of three-factor learning on such chips are limited. In a work by Mikaitis et al.,91 the authors show the effectiveness of this learning rule in solving the problem of credit assignment in the Pavlovian conditioning task on the Spinnaker120 chip. The proposed solution was compared with the GPU-based alternative, where neuromorphic implementation has shown a reduced runtime when scaling the number of synapses. Rostami et al.89 show an implementation of E-prop in the Spinnaker2 prototype.121 They compare the three-factor method with BPTT, matching the performances of ANN models on the Google Speech Commands dataset.122 Uludag� et al.88 used Loihi2110 to create a model inspired by the basal ganglia to solve the go/ no-go task, where synaptic plasticity was modulated by a signal that mimics the role of dopamine. A growing body of work showcases the effectiveness of three-factor learning on custom-made neuromorphic platforms. Recently, Frenkel and Indiveri introduced the ReckOn neuromorphic accelerator to train recurrent neural networks.105 This chip also enables three-factor learning based on the adapted E-prop algorithm. They demonstrate the feasibility of on-chip training via the aforementioned algorithm to obtain a network-solving navigation task with similar effectiveness to BPTT. In previous work introducing ODIN (onlinelearning digital spiking neuromorphic processor) and SPOON

| Platform | No. of neurons, | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| and author | no. of synapses | Learning algorithm | Energy usage | Task | Dataset | Performance | Technology |

| ODIN chip, Frenkel et al. 92 |

256 neurons (10 used), 64,000 synapses |

spike-driven synaptic plasticity (SDSP) for on-chip online learning; BPTT for off-chip learning |

prediction cost: 15 nJ |

image classification | 6,000 MNIST samples (16 × 16 downsampled) |

accuracy: off-chip learning: 91.4%; on-chip learning: 84.5% |

digital, 28-nm FDSOI CMOS |

| SPOON chip, Frenkel et al. 87 |

Conv. core: $10.5 \times 5$ kernels, 256 synapses (parameters); FC (fully connected) core: 138 neurons, 64,000 synapses |

direct random target projection algorithm 123 for on-chip learning; BPTT for off-chip learning |

prediction cost: MNIST: 313 nJ; NMNIST: 665 nJ |

image classification | MNIST, N-MNIST | accuracy (MNIST/ NMNIST): off-chip learning: 97.5%/ 93.8%; on-chip learning: 95.3%/93% |

digital, 28-nm FDSOI CMOS |

| 10-nm FinFET chip, Chen et al. 82 |

4,096 neurons, 1 M synapses |

STDP, R-STDP for on-chip learning; BPTT for off-chip learning |

prediction cost: 1.0–1.7 μJ |

image reconstruction, de-noising, image classification |

MNIST, natural scene images |

accuracy (MNIST classification): on-chip learning, R-STDP: 89%; off-chip learning, BPTT: 98.60% |

digital, 10-nm FinFET CMOS |

| ReckOn chip, Frenkel and Indivieri 105 |

up to 256 recurrent neurons, 16 output neurons, 132,000 synapses (8-bit) |

modified E-prop algorithm |

prediction cost: 0.6–42 nJ; training step cost: 1.5–178 nJ |

hand gesture recognition, keyword spotting, navigation |

IBM DVS Gestures, Spiking Heidelberg Digits (KWS), synthetic |

accuracy: 87.3% (gestures), 90.7% (KWS), 96.4% (nav) |

digital, 28-nm FDSOI CMOS |

| Loihi 2, Uludağ et al. 88 |

up to 1,048,576 neurons, 120 M synapses (used: 8,381 neurons, 252,987 synapses) |

task solved by pre-configured neurons modulated with third factor |

single timestep cost: $\sim$ 5.665 $\mu J$ | go/no-go decision-making |

not specified | not applicable (focuses on evaluation of neuron models) |

digital, Intel 4 Process (7 nm) |

| SpiNNaker 1, Mikaitis et al. 91 |

up to 10,000 neurons, 10 M synapses |

neuromodulated STDP (three-factor learning algorithm) |

total power consumption: up to 1 W for all cores @ 180 MHz |

Pavlovian conditioning | custom setup for Pavlovian conditioning |

not stated (focuses on computational efficiency) |

digital, UMC 130-nm 1P8N CMOS |

| 65-nm image classification processor, Park et al. 84 |

2 × 200 hidden layer neurons |

modified segregated dendrites algorithm 85 | prediction cost: 236.5 nJ; training step cost: 254.3 nJ |

image classification | MNIST (on-chip experiments) | accuracy: 97.83% (on-chip training) |

digital, TSMC 65-nm LP CMOS |

(Continued on next page)

| Continued Table 2. |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| and author Platform |

no. of synapses No. of neurons, |

Learning algorithm | Energy usage | Task | Dataset | Performance | Technology |

| Rostami et al.89 SpiNNaker 2 prototype, |

20–360 recurrent 25,000 synapses neurons, |

E-prop algorithm | total training energy usage (estimated): 30 epoch training) 54.7 kJ (for entire |

keyword spotting | Google Speech Commands (GSC-12) |

accuracy: 91.12% | digital, 22-nm FDSOI |

| Buhler et al.86 analog-digital 40-nm hybrid processor, |

512 analog neurons | locally competitive algorithm |

prediction cost: 50.1 nJ |

image classification | MNIST | accuracy: 88% | digital-analog hybrid, 40-nm CMOS |

(spiking online-learning convolutional neuromorphic processor) chips,87 ,92 Frenkel et al. also demonstrated a successful deploy ment of reward-based on-chip learning to perform digit classifi cation on the MNIST dataset.93 Other research groups have also proposed their own chips with three-factor online learning capa bilities, showing their effectiveness and energy efficiency in the MNIST classification82 ,84 ,86

The relative scarcity of solutions implementing three-factor learning on neuromorphic chips points toward a possible unex plored research direction. Most modern neuromorphic systems support reward signals by design.124 Furthermore, a growing ecosystem of software development kits allows porting solutions based on three-factor learning to the dedicated hardware.125

LIMITATIONS AND CHALLENGES

Despite significant progress in three-factor learning for SNNs, several limitations and challenges remain. These challenges span theoretical, computational, and practical aspects and affect the scalability, biological plausibility, and real-world applicability of current models. The primary concerns include the following.

- (1) Simplified neuron models and network structures: many studies use simplified neuron models, such as the Hodgkin-Huxley model, leaky integrate-and-fire models, or Izhikevich models.13 ,102 These models often lack the biological diversity and complexity of real neurons, including a limited diversity of receptor actions, simplified neuron morphologies, and a lack of detailed modeling of cellular processes.36 ,100 Furthermore, network structures are often simplified, with limited spatial connectivity and inter-columnar connections, and sometimes consist of only a few layers. ,19 These simplifications can limit the generalizability of the findings and their applicability to real biological systems. ,11

- (2) Lack of real-world testing and global error propagation: a significant number of studies rely on simulations and syn thetic datasets, 4 ,47 with a lack of real-world testing and empirical validation. 1 ,41 Some models are tested in simple simulated environments and on simplified tasks, which limits their real-world applicability.20 ,90 Furthermore, many models lack a clear mechanism for global error propagation, which is crucial for complex learning tasks.35 ,39 Although some papers address credit assign ment, most models do not fully implement it.15 ,35 Some models use simplified or indirect forms of supervision that may not be sufficient for complex tasks. 3 ,22

- (3) Parameter tuning and scalability challenges: many models require careful parameter tuning for optimal per formance, , 6 ,49 and their performance can be sensitive to parameter choices.21 ,103 Furthermore, many models have limited scalability and are not tested on large-scale networks or complex tasks.14 ,83 Some models have high computational costs, which can limit their applica bility.16 ,29 Although some studies show scalability to some extent, they often highlight limitations when applied to more complex scenarios.37 ,66 There is also a need for more efficient algorithms that can scale to larger and more complex networks.12 ,42

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Three-factor learning in SNNs presents exciting opportunities to bridge biological plausibility and ML efficiency. Future research should focus on optimizing neuromodulatory mechanisms for improved credit assignment, enhancing scalability for large networks, and integrating three-factor learning with modern deep learning frameworks. In addition, efforts should be made to validate these models with real-world data and neuromorphic hardware to enable practical applications in AI, robotics, and cognitive computing. Cross-disciplinary collaborations will be essential in refining learning rules and expanding their applicability.

Research opportunities

Several sources highlight areas for improvement in the field of neuromodulation and plasticity in neural networks. A key challenge is to improve the scalability of current models. Many studies use simplified models and simulated data, and it is necessary to extend these models to larger, more complex networks and real-world datasets.5,6,47,90 For example, while some models demonstrate scalability to a certain extent, they often note limitations when applied to more complex scenarios or real-world data.4,8 Another key research area involves the exploration of novel learning rules and architectures. Many studies introduce new learning methods or variations on existing ones, such as STDP, but these often require further validation and testing in diverse contexts.8,10,21 For example, some studies propose new three-factor learning methods,11,62 while others explore different ways to modulate STDP.12,36 There is also a need to better understand how neuromodulators can be used for credit assignment in deep networks.17,18,39 Some studies suggest that neuromodulators can act as a third factor in Hebbian learning, but the specific mechanisms and implementation details need further exploration.15,35,62 Finally, the validation of computational models with experimental data is crucial. Many studies rely on simulations and lack direct empirical validation.32,34,126 Future research should focus on bridging the gap between theoretical models and experimental findings.7,16,46

Interdisciplinary approaches

The sources strongly suggest that interdisciplinary collaboration is essential for progress in this field. The most successful studies often involve teams from diverse backgrounds, including neurobiology, ML, computer science, and robotics.23,90,127 By combining expertise from different fields, researchers can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interactions between neuromodulation, plasticity, and learning.1,79,101 Specifically, integrating biological insights into AI and ML models can lead to more robust and adaptable systems.4,27,40 For example, modeling the effects of neuromodulators like dopamine, acetylcholine, and norepinephrine can lead to more sophisticated learning algorithms.11,18,31 The study of astrocytes and their role in neuromodulation also opens up new avenues for exploration.100 Furthermore, understanding how the brain implements credit assignment, working memory, and decisionmaking processes can guide the development of novel AI architectures.15,33,90 In summary, the future of this field lies in combining cutting-edge computational techniques with a deep understanding of biological mechanisms. By embracing interdisciplinary approaches, researchers can push the limits of what is possible and develop more powerful and biologically plausible AI systems.11,19,21

CONCLUSIONS

This review has provided an overview of three-factor learning in SNNs, highlighting its significance in bridging biological plausibility and ML efficiency. The inclusion of neuromodulatory signals as a third factor improves credit assignment, adaptive learning, and long-term synaptic modifications, making SNNs more suitable for real-world applications. The key insights from this review emphasize the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration between neuroscience, AI, and robotics. Advances in neuromorphic computing, biologically inspired algorithms, and novel encoding strategies continue to drive improvements in network scalability, learning efficiency, and cognitive modeling. Although significant progress has been made, challenges such as model validation with real-world data, scalability limitations, and computational efficiency remain critical research areas. Future research should focus on integrating three-factor learning into scalable deep learning frameworks, optimizing neuromodulatory mechanisms for more biologically plausible credit assignment, and leveraging neuromorphic hardware for energy-efficient processing. By combining theoretical models with experimental validation and cross-domain collaboration, researchers can further refine learning rules and develop robust, adaptive systems. Ultimately, the future of three-factor learning lies in its ability to integrate insights from biological systems into AI, enabling more efficient, flexible, and human-like learning in neural networks. As the field advances, continued interdisciplinary efforts will be key to unlocking new possibilities in AI, cognitive computing, and robotics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 857533 and from the International Research Agendas Programme of the Foundation for Polish Science, no. MAB PLUS/2019/13. The publication was created within the project of the Minister of Science and Higher Education ''Support for the activity of Centers of Excellence established in Poland under Horizon 2020'' on the basis of contract number MEiN/2023/DIR/3796.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

DECLARATION OF GENERATIVE AI AND AI-ASSISTED TECHNOLOGIES IN THE WRITING PROCESS

During the preparation of this work, the authors used Gemini and ChatGPT in order to validate text style coherency and paraphrase chosen sentences. After using these services, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j. patter.2025.101414.

REFERENCES

-

- Richards, B.A., Lillicrap, T.P., Beaudoin, P., Bengio, Y., Bogacz, R., Christensen, A., Clopath, C., Costa, R.P., de Berker, A., Ganguli, S., et al. (2019). A deep learning framework for neuroscience. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 1761–1770. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-019-0520-2.

-

- Zenke, F., Agnes, E.J., and Gerstner, W. (2015). Diverse synaptic plasticity mechanisms orchestrated to form and retrieve memories in spiking neural networks. Nat. Commun. 6, 6922. https://doi.org/10.1038/ ncomms7922.

-

- Najarro, E., and Risi, S. (2020). Meta-learning through Hebbian plasticity in random networks. Preprint at arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv. 2007.02686.

-

- Mozafari, M., Ganjtabesh, M., Nowzari-Dalini, A., Thorpe, S.J., and Masquelier, T. (2019). Bio-inspired digit recognition using reward-modulated spike-timing-dependent plasticity in deep convolutional networks. Pattern Recogn. 94, 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2019. 05.015.

-

- Bellec, G., Scherr, F., Hajek, E., Salaj, D., Legenstein, R., and Maass, W. (2019). Biologically inspired alternatives to backpropagation through time for learning in recurrent neural nets. Preprint at arXiv. https://doi. org/10.48550/arXiv.1901.09049.

-

- Bellec, G., Scherr, F., Subramoney, A., Hajek, E., Salaj, D., Legenstein, R., and Maass, W. (2020). A solution to the learning dilemma for recurrent networks of spiking neurons. Nat. Commun. 11, 3625. https://doi.org/10. 1038/s41467-020-17236-y.

-

- Sutton, N.M., and Ascoli, G.A. (2021). Spiking Neural Networks and Hippocampal Function: A Web-Accessible Survey of Simulations, Modeling Methods, and Underlying Theories. Preprint at bioRxiv.

-

- Yi, Z., Lian, J., Liu, Q., Zhu, H., Liang, D., and Liu, J. (2023). Learning rules in spiking neural networks: A survey. Neurocomputing 531, 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2023.02.026.

-

- Hebb, D.O. (1949). The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory (Wiley).

-

- Fre´ maux, N., and Gerstner, W. (2015). Neuromodulated Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity, and Theory of Three-Factor Learning Rules. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncir.2015.00085.

-

- Gerstner, W., Lehmann, M., Liakoni, V., Corneil, D., and Brea, J. (2018). Eligibility Traces and Plasticity on Behavioral Time Scales: Experimental Support of NeoHebbian Three-Factor Learning Rules. Front. Neural Circ. 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncir.2018.00053.

-

- Pawlak, V., Wickens, J.R., Kirkwood, A., and Kerr, J.N.D. (2010). Timing is not everything: neuromodulation opens the STDP gate. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00146.

-

- Tiesinga, P.H.E., Fellous, J.-M., Jose´ , J.V., and Sejnowski, T.J. (2001). Optimal information transfer in synchronized neocortical neurons. Neurocomputing 38–40, 397–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-2312(01) 00464-7.

-

- Florian, R. (2005). A reinforcement learning algorithm for spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Symposium on Symbolic and Numeric Algorithms for Scientific Computing (SYNASC'05) (IEEE). https://doi.org/10.1109/SYNASC.2005.13.

-

- Fre´ maux, N., Sprekeler, H., and Gerstner, W. (2013). Reinforcement Learning Using a Continuous Time Actor-Critic Framework with Spiking Neurons. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1003024. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003024.

-

- Pedrosa, V., and Clopath, C. (2017). The role of neuromodulators in cortical plasticity. A computational perspective. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsyn.2016.00038.

-

- Brzosko, Z., Mierau, S.B., and Paulsen, O. (2019). Neuromodulation of Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity: Past, Present, and Future. Neuron 103, 563–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2019.05.041.

-

- Aljadeff, J., D'amour, J., Field, R.E., Froemke, R.C., and Clopath, C. (2019). Cortical credit assignment by Hebbian, neuromodulatory and

-

inhibitory plasticity. Preprint at arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv. 1911.00307.

-

- Sporns, O., and Alexander, W.H. (2002). Neuromodulation and plasticity in an autonomous robot. Neural Netw. 15, 761–774. https://doi.org/10. 1016/S0893-6080(02)00062-X.

-

- Alnajjar, F., Mohd Zin, I.B., and Murase, K. (2009). A Hierarchical Autonomous Robot Controller for Learning and Memory: Adaptation in a Dynamic Environment. Adaptive Behavior 17, 179–196. https://doi.org/10. 1177/1059712309105814.

-

- Hoerzer, G.M., Legenstein, R., and Maass, W. (2012). Emergence of complex computational structures from chaotic neural networks through reward-modulated Hebbian learning. Cereb. Cortex 24, 677–690. https:// doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhs348.

-

- Kopsick, J.D., Tecuatl, C., Moradi, K., Attili, S.M., Kashyap, H.J., Xing, J., Chen, K., Krichmar, J.L., and Ascoli, G.A. (2022). Robust resting-state dynamics in a large-scale spiking neural network model of area CA3 in the mouse hippocampus. Cogn. Comput. 15, 1190–1210. https://doi. org/10.1007/s12559-021-09954-2.

-

- Schmidgall, S., and Hays, J. (2023). Synaptic motor adaptation: A threefactor learning rule for adaptive robotic control in spiking neural networks. Preprint at arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.01906.

-

- Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br. Med. J. 372, n71. https://doi.org/10. 1136/bmj.n71.

-

- Kitchenham, B., Pearl Brereton, O., Budgen, D., Turner, M., Bailey, J., and Linkman, S. (2009). Systematic literature reviews in software engineering – A systematic literature review. Inf. Software Technol. 51, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2008.09.009.

-

- Marder, E., and Thirumalai, V. (2002). Cellular, synaptic and network effects of neuromodulation. Neural Netw. 4–6, 479–493. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0893-6080(02)00043-6.

-

- Lavigne, F., and Darmon, N. (2008). Dopaminergic neuromodulation of semantic priming in a cortical network model. Neuropsychologia 46, 3074–3087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.06.019.

-

- Suvrathan, A. (2018). Beyond STDP–towards diverse and functionally relevant plasticity rules. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 54, 12–19. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.conb.2018.06.011.

-

- Fre´ maux, N., Sprekeler, H., and Gerstner, W. (2010). Functional requirements for reward-modulated spike-timing-dependent plasticity. J. Neurosci. 22, 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6249- 09.2010.

-

- Soltani, A., and Wang, X.-J. (2006). A biophysically based neural model of matching law behavior: melioration by stochastic synapses. J. Neurosci. 26, 3731–3744. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5159-05.2006.

-

- Talanov, M., Vallverdu´ , J., Distefano, S., Mazzara, M., and Delhibabu, R. (2015). Neuromodulating Cognitive Architecture: Towards Biomimetic Emotional AI. In IEEE 29th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications (AINA) (IEEE), pp. 587–592. https://doi.org/10.1109/AINA.2015.240.

-

- Froemke, R.C. (2015). Plasticity of Cortical Excitatory-Inhibitory Balance. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 38, 195–219. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurevneuro-071714-034002.

-

- Gruber, A.J., Dayan, P., Gutkin, B.S., and Solla, S.A. (2003). Dopamine modulation in a basal ganglia-cortical network of working memory. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 16, 935–942.

-

- Edeline, J.-M. (2012). Beyond traditional approaches to understanding the functional role of neuromodulators in sensory cortices. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00045.

-

- Richards, B.A., and Lillicrap, T.P. (2019). Dendritic solutions to the credit assignment problem. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 54, 28–36. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.conb.2018.08.003.

-

- Foncelle, A., Mendes, A., Je'drzejewska-Szmek, J., Valtcheva, S., Berry, H., Blackwell, K.T., and Venance, L. (2018). Modulation of spike-timing

- dependent plasticity: towards the inclusion of a third factor in computational models. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fncom.2018.00049.

-

- Legenstein, R., Chase, S.M., Schwartz, A.B., and Maass, W. (2009). Functional network reorganization in motor cortex can be explained by reward-modulated Hebbian learning. In NIPS'09: Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Y. Bengio, D. Schuurmans, J.D. Lafferty, C.K.I. Williams, and A. Culotta, eds., pp. 1105–1113.

-

- Mozafari, M., Kheradpisheh, S.R., Masquelier, T., Nowzari-Dalini, A., and Ganjtabesh, M. (2018). First-Spike-Based Visual Categorization Using Reward-Modulated STDP. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 29, 6178–6190. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2018.2826721.

-

- Whittington, J.C.R., and Bogacz, R. (2019). Theories of error back-propagation in the brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 235–250. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.tics.2018.12.005.

-

- Yuan, M., Wu, X., Yan, R., and Tang, H. (2019). Reinforcement learning in spiking neural networks with stochastic and deterministic synapses. Neural Comput. 31, 2368–2389. https://doi.org/10.1162/neco\_a\_01238.

-

- Liu, Y.H., Smith, S., Mihalas, S., Shea-Brown, E., and Su¨ mbu¨ l, U. (2021). Cell-type–specific neuromodulation guides synaptic credit assignment in a spiking neural network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2111821118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2111821118.

-

- Durstewitz, D. (2006). A Few Important Points about Dopamine's Role in Neural Network Dynamics. Pharmacopsychiatry 39, 72–75. https://doi. org/10.1055/s-2006-931499.

-